I really thought that Socratic Seminars were something that happened in AP English classes in high school or at the college level until I was hired at a particular elementary school several years ago. The principal told me that using the Socratic Method for monthly book discussions was something they did to bring the school together around a common theme and he handed me a book to read to participate. He shared that the school leadership team had decided to try using the Socratic Method because they had noticed that the students seemed to think that there was not one right answer to every question, and they wanted to change that impression using this method.

The staff strongly felt that by learning to have open, student-led discussions, they could change the culture of the school and encourage open mindedness.

As I read the book about Socratic seminars for elementary students, I learned that this type of student-led discussion, based on Socrates’ method of student inquiry rather than teacher lecture, encourages student ownership, deep thinking, critical questioning, academic vocabulary usage, and a sense of community. Although the teacher is seemingly offstage, a meaningful and effective Socratic Seminar only occurs through intentional

planning. Socratic seminars are named for Socrates’ belief in the power of asking questions, prize inquiry over information and discussion over debate. Socratic Seminars acknowledge the highly social nature of learning and align with the work of John Dewey, Lev Vygotsky, Jean Piaget, and Paulo Freire. Socratic Seminars are defined as formal discussion, based on a text, in which open-ended questions are asked. Within the context of the discussion, students listen closely to the comments of others, thinking critically for themselves, and articulate their own thoughts and their responses to the thoughts of others. The students learn to work cooperatively and to question intelligently and with respect for their classmates. As I read more and visited

some classrooms in action at the school, I saw the impact of this approach to discussions around books and became a fan of the method.

These are some of the most important aspects in order to make Socatric seminars for elementary students a TOTAL success:

CHOOSING A TEXT

Socratic seminars work best with authentic texts that invite natural inquiry with an ambiguous and appealing short story, a pair of contrasting primary documents in social studies, or an article on a controversial approach to an ongoing scientific problem. In the case of my school, we choose books across a common theme to explore the topic of the month for the school with a rich text that offers cross-content and real-world connections. We often use a whole novel as the basis of a Socratic Seminar in the upper grades and picture books in the lower grades.

PREPARING THE STUDENTS

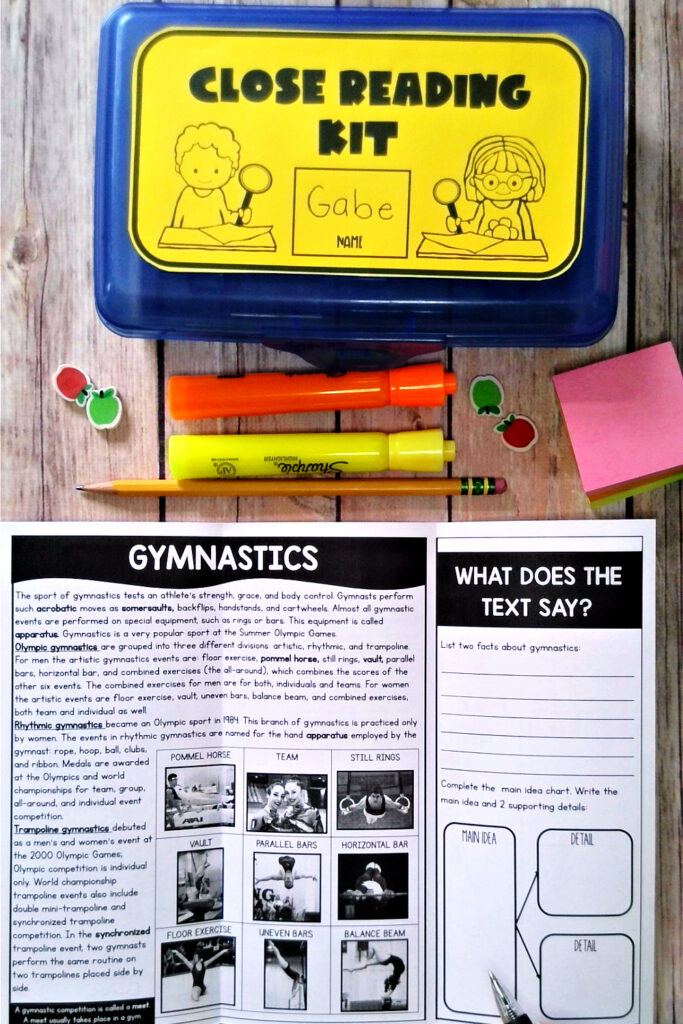

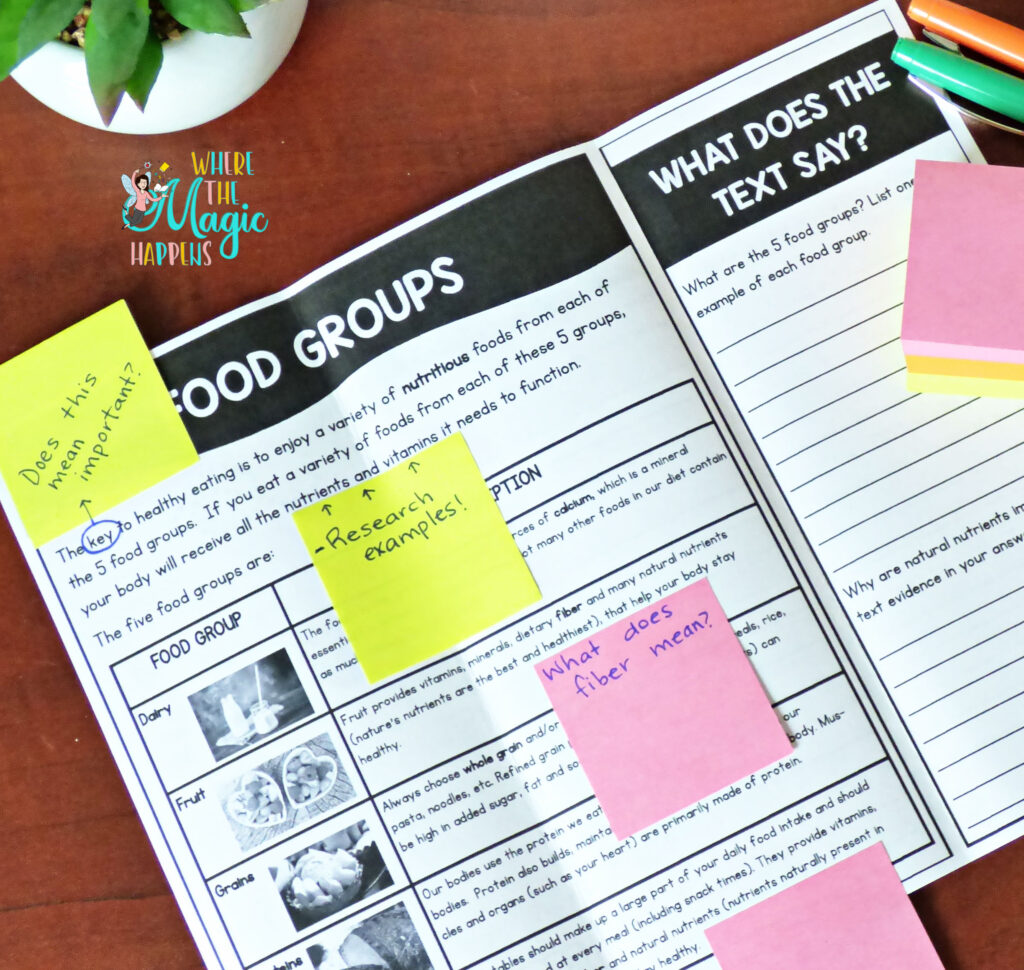

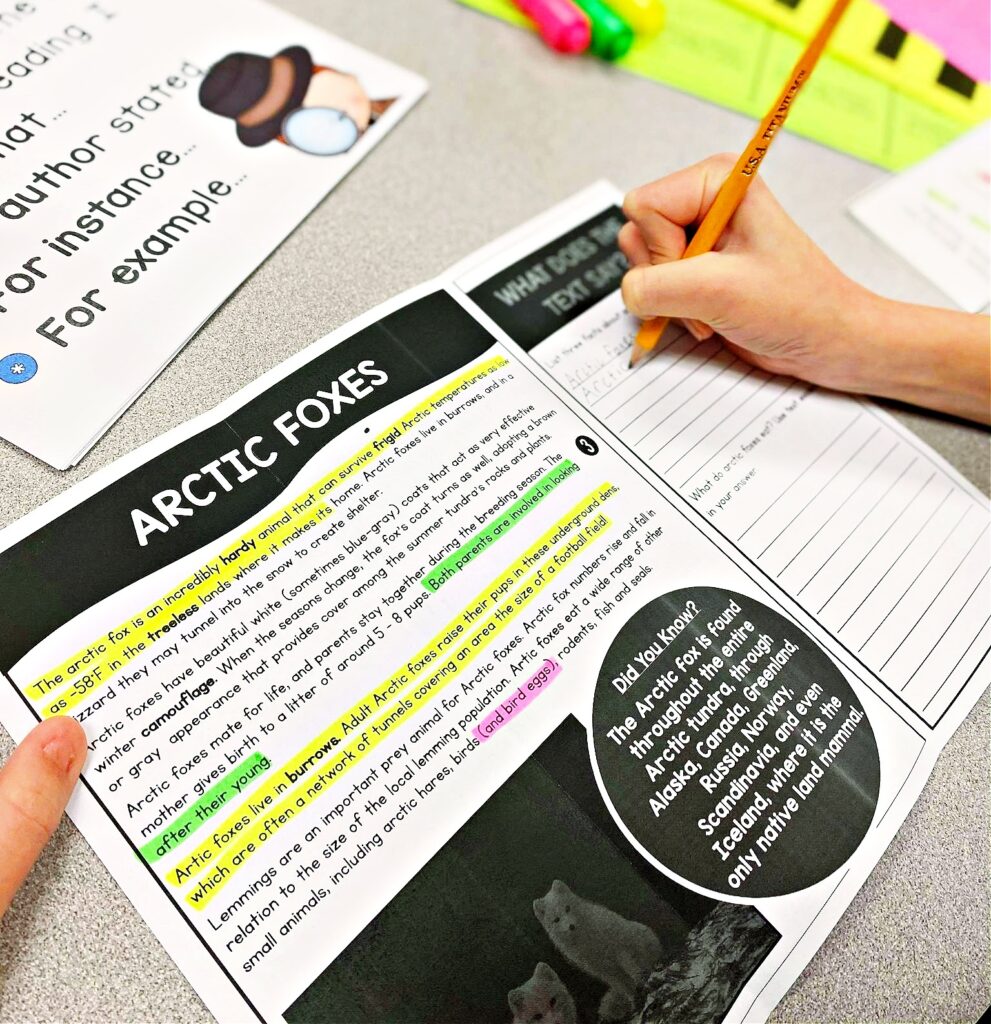

While students should read carefully and prepare well for every class session, it is usually best to tell students ahead of time when they will be expected to participate in a Socratic Seminar for this particular text. Because seminars ask students to keep focusing back on the text, you may distribute sticky notes for students to use to

annotate the text as they read. For the younger grades, the teacher often read the book to the children several times during the week before the school wide discussion time and made the book available to the students to explore individually. In the upper grades, we had a limited number of copies of the books and the teacher often used the book during the read aloud time each day but again made the book available for individual exploration.

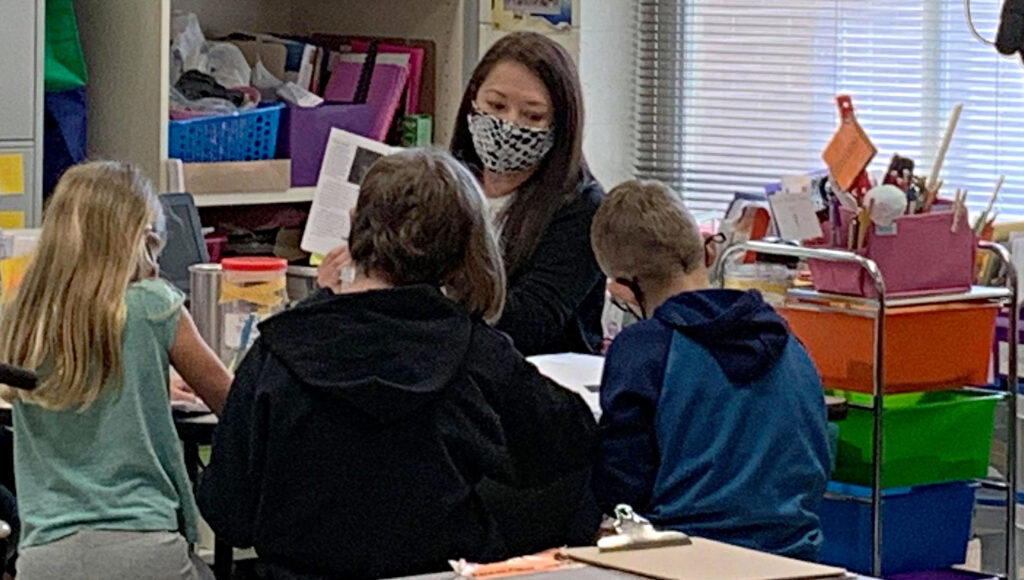

GETTING PHYSICAL

Arranging the furniture a bit differently facilitates Socratic seminars for elementary students. A seminar is best done in a circle, where students are equal and I (as a facilitator and not a participant) am on the outside. There are three ways to do that based on the class size and dynamics: one giant circle for all students, a fishbowl style (where the participants in an inner circle have a discussion and the participants in an outer circle coach the inner circle), or multiple smaller circles within the classroom so that it is easier for all the children to have the opportunity to talk.

PREPARING THE QUESTIONS

Though students were eventually given responsibility for running the entire session, the teacher usually fills the role of discussion leader as students learn about seminars and questioning. Generate as many open-ended questions as possible, aiming for questions whose value lies in their exploration, not their answer.

Starting and ending with questions that relate more directly to students’ lives, so the entire conversation is rooted in the context of their real experiences. I always prepared some discussion questions of my own, even when the students took over the discussion so I could stimulate the discussion if needed.

ESTABLISHING STUDENT EXPECTATIONS

Because student inquiry and thinking are central to the philosophy of Socratic seminars, it is an important to include students in the development of norms for the seminar. Begin by asking students to differentiate between behaviors that characterize debate (persuasion, prepared rebuttals, clear sides) and those that characterize discussion (inquiry, responses that grow from the thoughts of others, communal spirit). Ask students to hold themselves accountable for the norms they agree upon. Class charts that listed the norms were often useful in the beginning. In the younger grades, we taught sentence starters for the children to use as we found they needed the language to generate questions and comments. Sentence starters like these below can enhance respectful discussion:

o I wonder why…

o I have a question about…

o I agree/disagree with…because…

o That reminds me of…

o I don’t understand…

o I predict…

o On page ____ it says______ so I think…

o ____ could you please clarify what you mean when you said_____

o I would like to add to what ___ was saying.

o I had a different opinion to what ___ was saying because I thought _____

o I came to the conclusion ____ because …

ESTABLISHING YOUR ROLE

Though you may assume leadership through determining which open-ended questions students will explore (at first), the teacher should not see him or herself as a significant participant in the pursuit of those questions. You may find it useful to limit your participation to helpful reminders about procedures (e.g., “Maybe this is a good time to turn our attention back the text?” “Do we feel ready to explore a different aspect of the text?”). Resist the urge to correct or redirect, relying instead on other students to respectfully challenge their peers’ interpretations or offer alternative views. Gradual release leading the discussion to the students leads to their active participation.

GETTING BETTER

Socratic seminars require assessment that respects the nature of student- centered inquiry to their success. The measure of success is reflection, both on the part of the teacher and students, on the degree to which text-centered student talk dominated the time and work of the session. Reflective writing asking students to describe their participation and set their own goals for future seminars can be effective as well.

Understand that, like the seminars themselves, the process of gaining capacity for inquiring into text is more important than “getting it right” at any point.

RESOURCES TO USE WITH SOCRATIC SEMINARS

SUGGESTED SHOPPING LIST

L

Leave a Reply